Picking Up CS Basics With Rust

Finding my passion for software engineering late (in this case meaning a few years after college) meant that my first real taste of a programming language was with JavaScript. I went through a career transition like many others with a bootcamp, which focused on teaching us skills that could be immediately applied to real jobs, i.e. JavaScript (also React, but it really is just part of JavaScript). However, I wasn’t satisfied with what I was learning; I wanted more; I wanted to learn what goes on in the layers below that have been abstracted away from us. So I ventured into learning Rust next.

It’s been more than a year since I started learning Rust at this point, so I don’t remember the exact reasons why I chose Rust over other options like C or C++. It includes influence from prominent personalities (ThePrimeagen mention!), available learning resources (The Rust Book is awesome), and just outright curiosity. What I do remember was that I really struggled with trying to learn Rust. It was hard! The compiler was throwing so many errors my way that I didn’t understand; I kept running into the infamous borrow checker.

But with enough time, persistence, and determination, I now proudly say that I love using Rust. I still struggle a lot, but I find that I learn a lot more about software when I use Rust. Coming from a bootcamp, I lack a lot of foundational knowledge on how computers work; Rust exposes me to many of these concepts, pointing me to knowledge gaps that I can then fill.

For the rest of this article, I describe 5 concepts I learnt while learning Rust that helped me better understand software in general. These concepts are far from exhaustive; they are only a subset of what I think are basic concepts about software engineering that I learnt from picking up Rust. They are also in no way shape or form instructional. I’m not an expert on these topics, and am still very much learning as I go.

1. Memory must be managed

When I started learning JavaScript, there was no notion of memory management. I declared variables, assigned values to them, and called it a day. There was no need for me to think about how the values are stored by the program at all.

However, the reality is of course very different. It’s not that I somehow didn’t have to manage memory; it’s that the memory was being managed for me by JavaScript’s runtime (usually V8) using a concept called garbage collection. Basically, the runtime keeps track of variables in the program, and frees the memory that is no longer required back to the host operating system, i.e. collects the garbage.

So if Rust doesn’t have a garbage collector, then how is memory managed?

Manually by you and me!

The code we write defines how the memory is managed; WYSIWYG. I still have a lot to learn about what it means to manage memory. For now, my understanding is that I have to keep in mind when and where variables are allocated in memory, and when the memory is freed and returned to the host operating system. If memory is not properly managed, it can lead to all sorts of bugs, or worse still, vulnerabilities in the program that can be exploited by bad actors.

That’s why garbage collection was created, it relieves the programmer from having to do manual memory management. It is a solution to reduce memory bugs, and is a feature of many popular languages, such as Go, Python, and the aforementioned JavaScript. However, it is far from a perfect solution. As with many things in software, there are tradeoffs. For example, Discord once switched a codebase from Go to Rust because garbage collection was causing their service to miss their performance targets due to the garbage collection runs taking up precious time and CPU resources.

Rust instead tries to ensure memory safety with its concept of ownership. Part of being a beginner means not knowing what I don’t know. Because Rust has all these elaborate rules, I am forced to learn about them to better understand what is going on and why these rules were created in the first place. That’s also why I’m loving Rust! I find that I learn more about the fundamentals of software and computer science as I continually use Rust.

2. Stack vs heap

In the previous section, I talked about having to manage memory. In a sense, this section can be a subsection of the previous, but I thought the learning for me was significant enough to warrant a separate section of its own.

You may have heard of the Call Stack in JavaScript. The stack that I’m referring to in this section is similar, but the focus is on where data is stored in memory when our program runs.

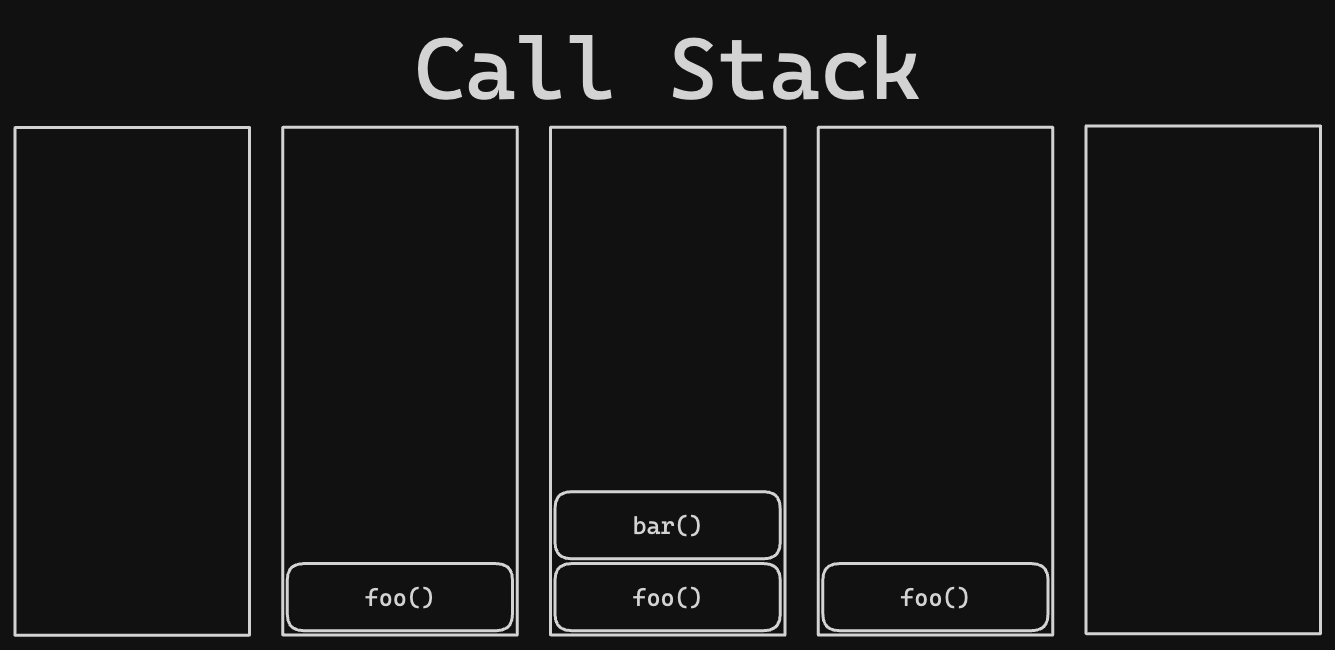

The stack is a region of memory where data is “stacked” on top of each other, hence its name, and follows a LIFO (Last-In-First-Out) principle. In JavaScript, the call stack is used to keep track of where the program is at in a script that calls multiple functions. When we call a function, we push a stack frame representing that function onto the stack. Nested function calls will push more frames onto the stack. The top-most frame represents the function within which the program is in. When a function returns, we pop the top-most frame and return control to the next frame below it.

function foo() {

bar();

}

foo();

Using the sample code above, the call stack might look like the following from the start to end of the program’s lifetime.

For stack memory, we take this concept and extend it to data. When we assign data to a variable, we push a frame onto the stack. However, instead of a reference to a function, we push the actual data onto the stack. For example, when we assign a variable let x = 7;, the number 7 is literally pushed onto the stack (in binary representation of course).

The stack is also scoped. In Rust, this is the block scope defined by {}. At the closing brace, values that were defined but not moved elsewhere are dropped from memory, i.e. popped off the stack. This is similar to how JavaScript pops function frames off the call stack once the function returns.

What if we want to push an array onto the stack? (In this case, I am referring to arrays as how JavaScript defines them. The Rust equivalent is called a Vec.) Imagine the following code:

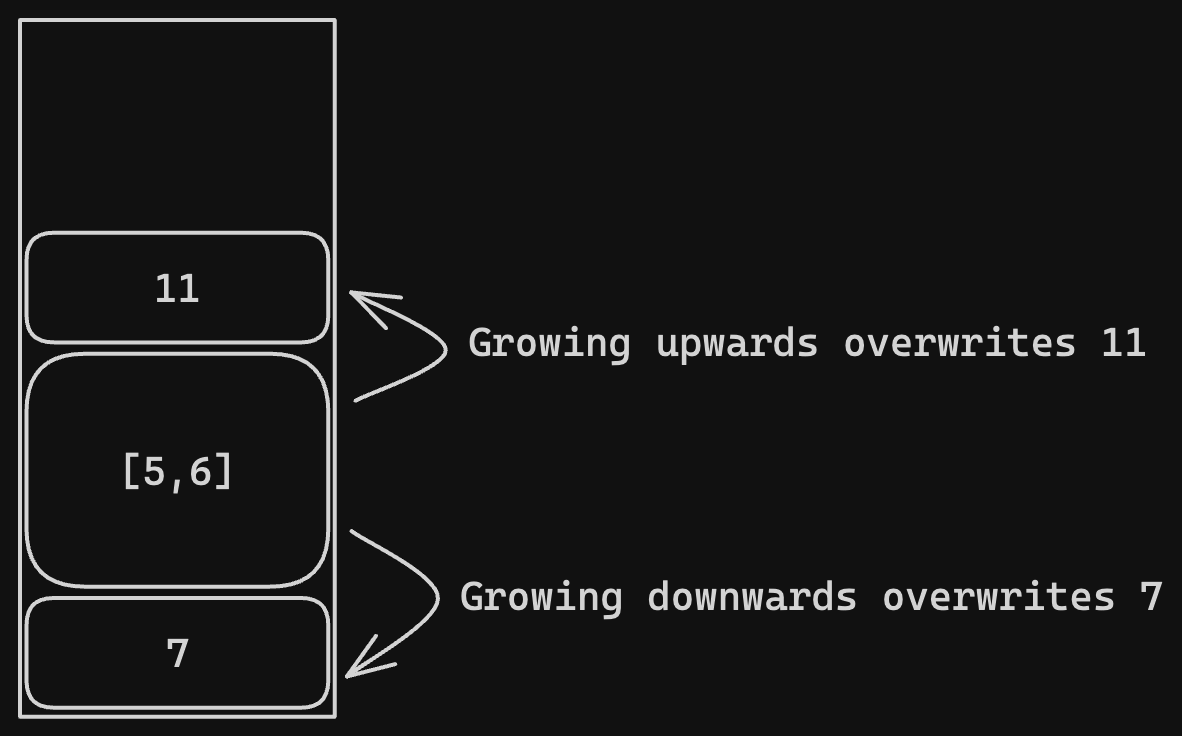

let x = 7;

let arr = [5, 6];

let y = 11;

arr.push(3);

We first push 7 onto the stack. Next, when we declare arr, we push the values 5 and 6 onto the stack along with some unique identifier to indicate that they belong in an array. 11, the value of y, is pushed onto the stack after that. Then we come to arr.push(3). What should happen here? Because it’s a stack, the values for x and y are right next to the array.

If we try to add a value to the array on either end (“top” or “bottom”), we will overwrite data that already existed in that memory because we can’t edit data in the middle of the stack; we can only push or pop from the top. So this isn’t possible. Instead, we need to use the heap.

Unlike the stack, the heap does not require data to be packed next to one another. If we store an array on the heap, we can grow it in either direction so long as there is no other valid data stored at that memory address.

This is possible because heap memory is managed by the operating system. If there is other data preventing the array from growing, the operating system can reassign another valid memory address for our program to use, so that we can keep growing our array.

In Rust, certain data types are automatically stored on the heap. Two examples are the String and Vec types, Vec being analogous to JavaScript arrays. If you have strings or arrays whose lengths will not change, you can use the str and array primitive types respectively instead. You can also choose to store values on the heap instead by using a keyword like Box, for example let on_heap: Box<u8> = Box::new(5);.

However, the heap is a separate memory location from the stack. Our program uses the stack to keep track of where it is in the program, so how can we reach data that is stored in the heap? This brings us to pointers.

Author’s Note: Recently, I came across videos that I thought were quite good from a YouTube channel called Core Dumped that goes in-depth about the stack and heap.

3. Pointers are a thing

Pointers are exactly that, they point to (or reference) something. Instead of storing data, pointers store the memory address of the data that they reference.

In JavaScript, values are either passed by value or by reference.

let x = 6;

let y = x;

y = 9;

console.log(x, y); // 6, 9

let foo = {

someKey: �some val�,

};

let bar = foo;

bar.someKey = �modified�;

console.log(foo.someKey); // �modified�

When we assign x to y, 6 is passed by value to y, i.e. copied from x and assigned to y. If we assign another value to y, only y changes because it is the sole owner of the value. For objects, when foo is assigned to bar, it is actually a reference to the underlying object that is passed to bar. So, when we change the value of someKey in bar, foo also gets changed.

This is sort of what pointers are like, at least that was how I first started to understand them.1

In JavaScript, the concept of a reference is implicit. Primitive values are passed by value; objects, arrays, and functions are passed by reference.

In Rust, references and pointers are explicit. We can declare a pointer using an ampersand as per the following:

fn main() {

let x = 6;

let y = &x; // y stores the memory address of x

}

If we modify x, y will change. Rust’s strict rules means that the example is more verbose, in particular I’ll discuss the mut keyword in point 5.

fn main() {

let mut x = 6;

let y = &mut x;

*y = 9;

println!("{y}"); // 9

println!("{x}"); // 9

// NOTE: y must be before x, not the other way around or on

// the same line, otherwise the Rust compiler will complain.

// due to the rules around borrowing

}

Note the use of the asterisk in the above example, it means that we want the value that is behind the pointer, i.e. to dereference y. In this case, because y is a pointer to an integer, we are saying that we want to change the integer that y references to 9. If we speak loosely in types, y has the type of &integer (reference to an integer). Trying to assign y directly to a number, like y = 9 means we have a mismatch in types. To make both side have the same type, we have to dereference y.

I only pointed to the start about pointers; there is so much more than what I have described here. I am also still learning about them, such as how pointers are useful and when to use them. There are also more complex uses of pointers, such as reference counting.

Side note: In Rust, what if we want to pass by value like in JavaScript?

fn main() {

let mut x = 6;

let y = x;

x = 9;

println!("{x}, {y}"); // 9, 6

}

In Rust, types that implement the Copy trait will be implicitly copied just like in JavaScript. (Traits are Rust’s way of saying that a type has a certain behaviour or implements a specific function.) Not all types implement Copy though. Instead, some of them implement the Clone trait which also allows the passing of data by value, but requires the user to explicitly state it, i.e. let foo = bar.clone();. You can also implement these traits on types that you create, so that your types can also be passed around by value.

4. There is more to arrays and objects

Let’s start with arrays. JavaScript arrays are resizable; Rust arrays are not.

When I used JavaScript arrays, I would just treat them as dynamically resizable lists of elements that I could modify whenever I needed to. However, when I peeled back the layers and explored how things work with Rust, there was so much more. So much goes on just to give us the convenience of having a dynamically-sized data structure at runtime.

I hinted at the difference earlier when I mentioned that in Rust, Vec is the type that is analogous to arrays in JavaScript. The array type does exist in Rust, but it is very different from JavaScript arrays. In Rust, an array is a fixed-size list of elements that can be stored on the stack. As explained above in #2. Stack vs Heap, we can’t change the size of elements that are stored on the stack, so we can store Rust arrays on the stack.

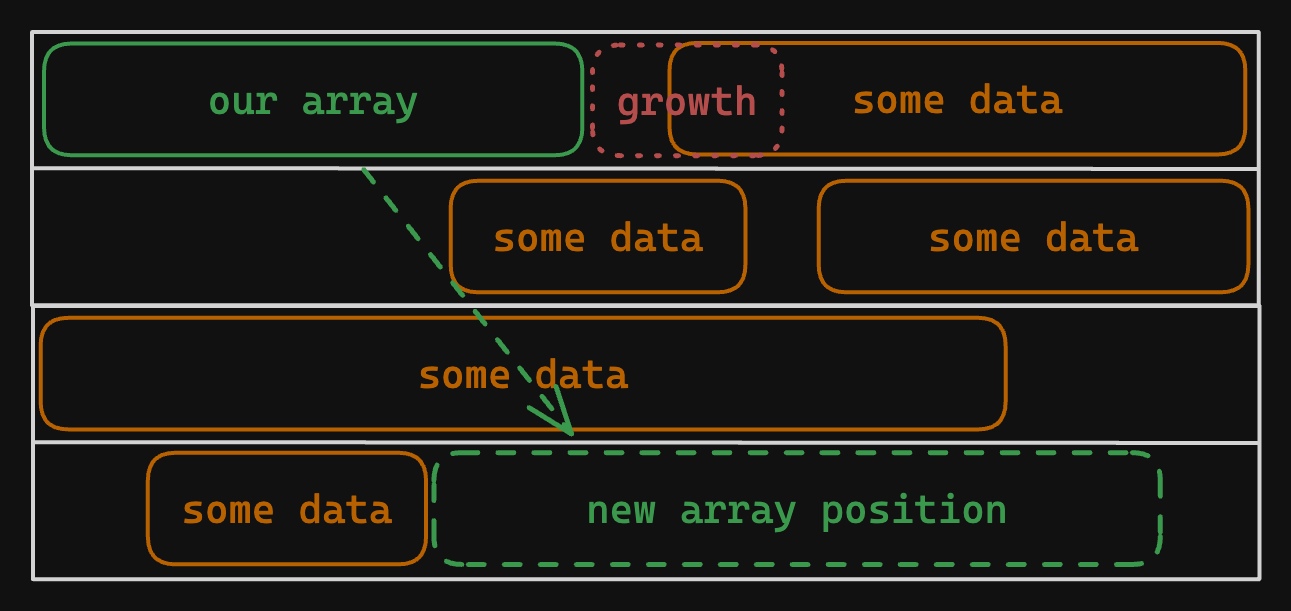

To get the dynamically resizable type (Vec), we move the data storage location from the stack to the heap. On the stack, we store a pointer to the Vec. Instead of just storing the memory address of the Vec, it will also contain two other values: length and capacity. Length is the number of values in the Vec; capacity is how many values the Vec can currently store.

Why is there a capacity when Vecs are supposed to be dynamically sizable?

If you recall from #2. Stack vs Heap, heap memory is managed by the operating system. The OS has to allocate memory for our program according to its needs. It can’t possibly allocate an infinite amount of memory. Even if it could, doing so would starve all other programs of memory on the heap. So the capacity is the current amount of memory that is allocated to the Vec.

When we push a value into a Vec, if length < capacity, the value gets added to the list of values and we increment length by 1.

However, if length = capacity, things get slightly more complicated.

First, Rust will have to determine how much more memory should be allocated for the Vec. This is determined by the growth factor of the data structure. For Rust Vecs, the factor is 2, which means the capacity doubles every time we need to add values beyond its current capacity. Next, the operating system has to find a suitable location in the heap that is able to fit contiguous data with the length of the capacity value. Lastly, the values in the pointer are updated to reflect the new memory location, length, and capacity.

This reallocation of memory comes at a cost. So, while pushing values into an array is on average O(1), hitting a reallocation would cause the push operation to take slightly longer.

That about covers the key parts about resizable lists (JS arrays or Rust Vecs) that I learnt from picking up Rust so far.

Next is objects. In JavaScript, we use objects for all sorts of purposes.

- Frequency counter pattern

- Hash table / Hash map / Dictionary / Associative array

- Storing state

- Modelling real-life objects

- Etc.

What I’ve come to learn is that there are actually two different kinds of data structures being used here. In Rust, they are struct and HashMap. In the examples that I listed, I would use HashMap for implementing the frequency counter pattern, whereas I would just use structs for storing state and modelling objects.

In terms of functional similarity, JavaScript objects would be more like a HashMap in Rust. That’s because we can change the properties that are in a JavaScript object; we can add and remove key-value pairs as needed.

So what’s the difference between structs and HashMaps?

As mentioned above, one of the key differences is that key-value pairs in a HashMap can be changed, while structs are fixed data structures. Dynamic vs fixed data, sound familiar? HashMaps are stored on the heap, while structs can be stored on the stack!

Think about it for a moment.

Like Vec, the amount of memory needed to store a HashMap is unknown at runtime. Recall that only data stored on the heap can grow or shrink the amount of memory it requires, because the program will coordinate with the operating system to allocate memory as needed. Thus, HashMaps must be stored on the heap.

On the other hand, structs are like templates. When we create a new struct, Rust knows exactly how much memory the struct requires because we can’t add or remove fields from a struct, so we can store structs on the stack. For example, primitive values like integers and booleans have a fixed size. Pointers to other data structures like Vec also have fixed sizes, so there is no issue storing them on the stack.

Unlike arrays, what I’ve realised is that I use the fixed data structure more than the dynamic one, i.e. structs more than HashMaps. I think this might not be just due to Rust though, because I also use a similar pattern of grouping primitive types into an interface when using TypeScript. In fact, structs are defined as a type composed of other types, which makes sense because I think a strict type system is what pushes me towards such a usage pattern.

To close off this section, learning Rust has shown me that data structures I took for granted are possible because of the abstractions created over more primitive underlying concepts. There is always more than meets the eye.

5. Be careful with mutability

You might have caught the use of the mut keyword in Rust when I wanted to make a variable mutable. This explicitness was a deliberate design choice for Rust, which is in stark contrast to JavaScript, where variables are always mutable. Depending on the declaration keyword used, variables can even change types!

The obvious one here is the let keyword in JavaScript, which by definition declares a re-assignable variable, and re-assignable is very much mutable.

How about const in JavaScript? By definition, variables declared with const can’t be reassigned, but if the value is an object, its properties can still be changed!

const x = 1;

x = 2; // Uncaught TypeError: Assignment to constant variable.

const foo = {};

foo.someProp = "hello world";

console.log(foo); // { someKey: "hello world" }

So there is no true immutability in JavaScript. After using Rust, I think I very much prefer Rust’s way, which is having immutability by default and requiring mutability to be made explicit. I think it helps to prevent a lot of subtle bugs that would otherwise be difficult to detect.

Side note: Rust does have a sort of reassignment with its concept of shadowing which allows you to assign different types to the same variable name. But here, the compiler simply refuses to compile your program if wrong types are used.

However, Rust goes much further than that. Rust is very strict about mutability, with its borrow checker having a sort of infamous reputation as something to “fight” when learning Rust. I won’t even attempt to go into the details of the borrow checker2. I rely a lot on error messages from the compiler and LSP (which are I think are EXCELLENT) to fix my code accordingly.

The basic rule is that “at any given time, you can have either one mutable reference or any number of immutable references.” Mutable references are explicitly defined in Rust with both the ampersand and the mut keyword.

fn main() {

let mut x = 9;

let y = &mut x;

*y = 11;

println!("{y}"); // 11

println!("{x}"); // 11

}

According to Rust, the rules make it possible to prevent data races at compile time. A data race is exactly as it suggests: a race. It typically happens when two or more pointers are trying to access the same data, and at least one pointer is being used to write data. It then becomes a race as to which pointer accesses the data first. If the writer accesses it first, the reader will read the new data, otherwise it will read the old data. I don’t think I need to explain why that could be an issue.

Another way to think about it is that mut means “exclusive access”. (I learnt this from Jon Gjengset, whom I think produces great educational content with and about Rust.) Imagine that a reference has exclusive access to a value. It can change the value to its heart’s content because no one else cares about the value. However, if access is no longer exclusive, there could be others that care about the value and use it for their purposes, so it could be problematic to have the value be mutable.

In essence, I say think deeply when choosing to make a variable mutable. Mutability is necessary, but after learning Rust, I think they should be used much more carefully and thoughtfully.

Closing

Thank you for making it this far. That concludes the 5 concepts I learnt from learning Rust that I thought helped me better understand software. Again, these are just what I learnt. They are in no way exhaustive or instructional.

Writing this article was very much an exercise for me to clarify and solidify my learnings as it was to share something useful with others. I hope you learnt something, or at least gained a better appreciation for stuff that goes on under the hood of what we use!

I look forward to learning even more broadly and deeply about the software I use. Perhaps I will write about my learnings then again.

As always, things are more complicated than they seem. This StackOverflow post seems to have some interesting answers, though I have not dived into the intricacies yet myself. ↩︎

If you’re curious, one resource I’m aware of is Rust for Rustaceans. I tried reading it at the end of 2023, but it was far too complicated for me to understand at that point. I do plan to get back to it sometime in the near-future though! ↩︎